How to Plan Your Week: A Science-Backed System That Actually Works

A 5-step weekly planning method built on research from cognitive psychology, circadian biology, and behavioral science. No productivity guru opinions, just what the studies say.

Here's a stat that should change how you think about planning: researchers found that simply making a specific plan for an unfinished task eliminates its mental burden, even if you haven't started the task yet (1). Not "reduces." Eliminates.

Most weekly planning advice boils down to "write a to-do list on Sunday and prioritize it." That's not planning. That's sorting. Real planning, the kind backed by decades of cognitive psychology, goes deeper. It accounts for how your brain actually processes goals, why you consistently underestimate how long things take, and why some hours of your day are worth three times more than others.

This is a 5-step method built on research from experimental psychology, circadian biology, and behavioral science. No productivity guru opinions. Just what the studies actually say.

Why Weekly Planning Works (According to Research)

Your brain treats unfinished tasks differently than completed ones. Psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik first documented this in 1927: incomplete goals create a kind of cognitive tension that occupies working memory until the task is resolved. You experience it as that nagging feeling that you're forgetting something. Neurologically, you are carrying it.

In 2011, E.J. Masicampo and Roy Baumeister ran a series of experiments testing whether planning could defuse this effect. Their finding: making a concrete plan for when and how you'll complete an unfinished goal completely eliminates its cognitive interference (1). The tasks didn't need to be done. They just needed a plan.

This matters for weekly planning because the act of scheduling your tasks isn't just organizational. It's neurological. You're freeing up working memory by giving your brain a "where and when" for each open loop.

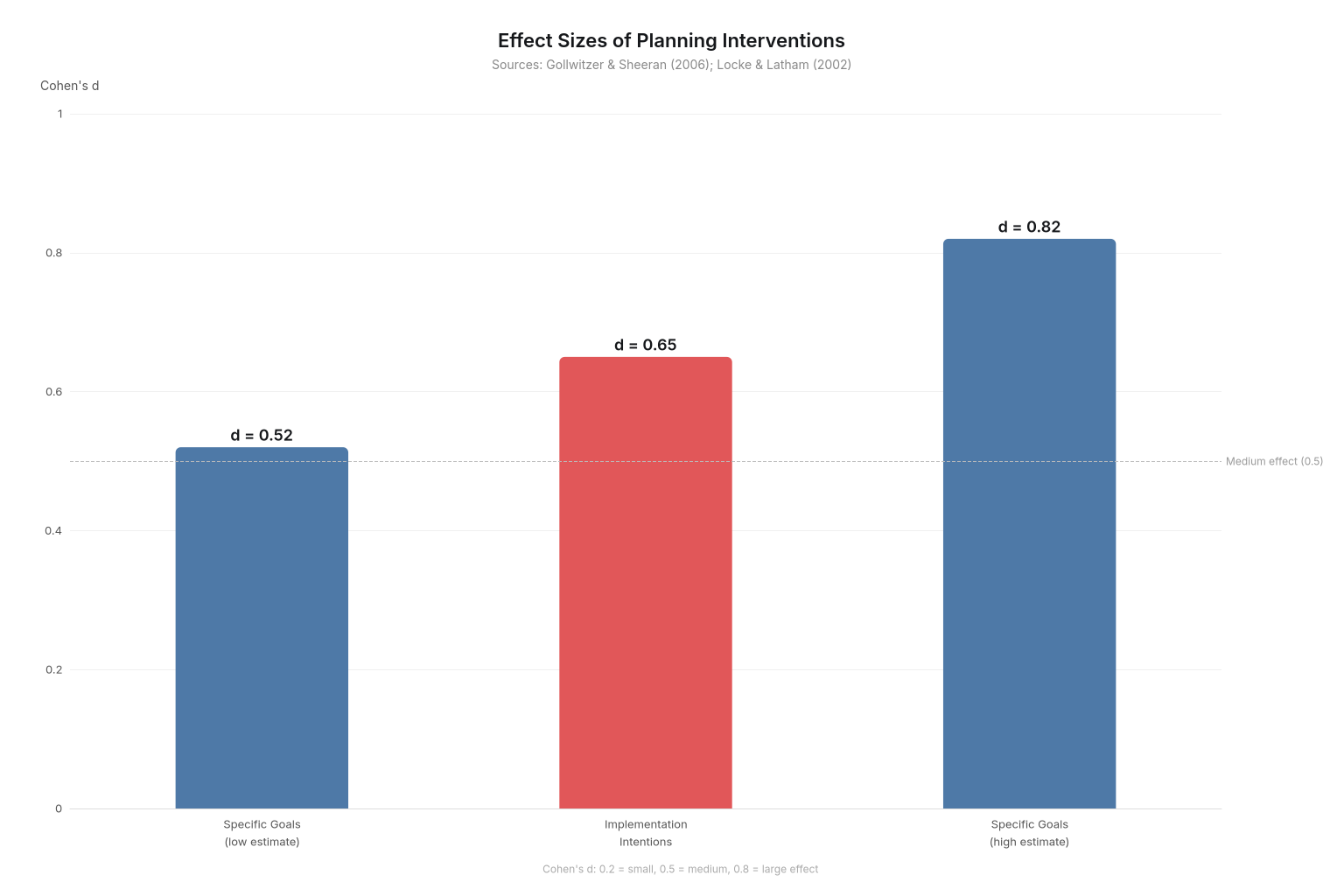

The effect gets stronger when your plans are specific. Peter Gollwitzer's research on implementation intentions (plans structured as "when X happens, I will do Y") shows a medium-to-large effect on goal attainment across 94 studies, with a Cohen's d of 0.65 (2). That's not a marginal improvement. For context, many widely-used medical interventions show smaller effect sizes.

And the goals themselves matter. Locke and Latham's 35-year review of goal-setting research found that specific, challenging goals consistently outperform vague intentions like "do your best," with effect sizes ranging from d = 0.52 to 0.82 across multiple meta-analyses (3). "Finish the Q1 report by Wednesday" works. "Be more productive this week" doesn't.

The Planning Fallacy (And How to Beat It)

There's a reason your weekly plans consistently fall apart by Wednesday. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky identified it in 1979: the planning fallacy (4). When estimating how long a task will take, people default to an "inside view." They imagine the specific steps, assume things will go smoothly, and arrive at an optimistic number. They almost never consult the "outside view," which is how long similar tasks actually took in the past.

This isn't about being bad at planning. It's a systematic cognitive bias. Buehler, Griffin, and Ross tested this across multiple studies in 1994 and confirmed it: people consistently underestimate completion times even when they have direct experience with the same type of task (5). Knowing you ran late last time doesn't help. Your brain still defaults to the optimistic scenario.

The fix is structural, not motivational. Two approaches backed by the research:

Reference-class forecasting. Instead of estimating from scratch, look at how long similar tasks took you in previous weeks. Check your calendar, time-tracking data, or old project timelines. Kahneman calls this the "outside view": it uses actual base rates instead of imagined best-case scenarios (4).

Buffer time. Add 25–50% to your time estimates for any task that involves thinking, creating, or coordinating with other people. This isn't pessimism. It's calibration. The 25% floor accounts for the average underestimation; the 50% ceiling covers tasks with high uncertainty or external dependencies.

Build both into your weekly planning process. You'll produce fewer tasks on your plan, and you'll actually finish the ones that are there.

How to Plan Your Week in 5 Steps

Step 1: Run a 15-Minute Weekly Review

Before planning forward, look backward. Pull up last week's plan and audit it:

- What got done? Note your completion rate. If you consistently finish only 60% of planned tasks, your plans are too ambitious, not your work ethic.

- What carried over? Anything that rolled over two weeks in a row either needs to be rescheduled with a real time commitment or removed entirely. Phantom tasks that linger week after week are cognitive dead weight.

- What surprised you? Unplanned tasks that consumed significant time reveal patterns. If client requests regularly derail your Tuesdays, stop scheduling deep work on Tuesdays.

The weekly review is where the planning fallacy gets corrected in practice. Your actual completion data from last week is the "outside view" Kahneman recommends (4). Use it.

Step 2: Identify 3–5 Priorities (Not 20)

Open a blank note and write down everything you want to accomplish this week. Then cross out everything except the 3–5 things that would make the week feel successful even if nothing else happened.

This isn't about having fewer tasks. You'll still handle emails, meetings, and small obligations. It's about knowing which outcomes matter. Locke and Latham's research is clear: specific, challenging goals produce higher performance than vague goals or long undifferentiated task lists (3). Your brain can hold about 3–5 meaningful objectives in active focus. Beyond that, priorities become noise.

For each priority, write it as a specific outcome: "Draft the investor update with Q4 metrics" instead of "Work on investor stuff." The specificity is what activates the goal-setting effect.

Step 3: Map Tasks to Your Energy Curve

This is the step most planning guides skip entirely, and the one that makes the biggest practical difference.

Your cognitive capacity isn't flat across the day. Circadian rhythm research shows a consistent pattern: attention and analytical ability rise through the morning, peak between roughly 10:00 and 14:00, drop during the post-lunch dip (14:00–16:00), and recover in the late afternoon before declining at night (6). This pattern isn't about being a "morning person." It's core body temperature, cortisol rhythms, and neural arousal following a predictable biological curve.

Facer-Childs and colleagues confirmed in 2018 that chronotype shifts this window but doesn't eliminate the pattern: morning types peak earlier, evening types later, but everyone has high and low periods (7). The post-lunch dip is nearly universal.

The practical application for weekly planning:

- Peak hours (your top 2–3 hours): Schedule your hardest priorities here. Deep analytical work, writing, strategic thinking, complex problem-solving. These are the hours where an hour of work produces two hours of output.

- Moderate hours: Meetings, collaborative work, email that requires thoughtful replies, lighter creative tasks.

- Low-energy hours (post-lunch dip, late afternoon fade): Administrative tasks, routine email, filing, scheduling, low-stakes decisions.

You don't need a precise energy score. Just ask: "When do I reliably do my best thinking?" and protect those hours for your Step 2 priorities. Most people already know the answer — they just don't plan around it.

If you've read our piece on time blocking, this dovetails directly. Time blocking gives your tasks specific time slots; energy mapping tells you which slots to put them in.

Step 4: Create Implementation Intentions

This is where planning becomes a psychological tool, not just an organizational one.

For each of your 3–5 priorities, write a plan in this format:

"When [time/day], I will [specific action] in [location/context]."

Examples:

- "When I sit down Monday at 9am, I will open the Q1 report document and write the revenue section."

- "When my 2pm meeting ends on Wednesday, I will spend 30 minutes reviewing the design mockups."

- "When I finish lunch on Thursday, I will call the three clients on my follow-up list."

This format isn't arbitrary. Gollwitzer's meta-analysis of 94 studies showed that implementation intentions (linking a specific behavior to a specific cue) produce a Cohen's d of 0.65 for goal attainment (2). The mechanism: your brain pre-loads the situation-response link, so when the cue arrives, the action feels automatic rather than requiring a decision.

A review by Hagger and Luszczynska in 2014 confirmed the effect holds across domains: health behavior, academic performance, professional tasks (8). It's one of the most replicated findings in behavioral science.

Notice the difference from a standard to-do list. "Write Q1 report" requires you to decide when, where, and how to start each time you see it. "Monday at 9am, revenue section, at my desk" has already made those decisions. That's the point.

Step 5: Build in Buffer Time

Take your planned week and add space. Specifically:

- Between major tasks: Add 15–30 minutes of unscheduled time. This absorbs the inevitable overrun from Step 4's implementation intentions and prevents one late task from cascading through your afternoon.

- Per day: Leave at least 20% of your working hours unscheduled. If you work 8 hours, that's roughly 90 minutes with nothing on the calendar. This is your shock absorber for unplanned requests, tasks that take longer than expected, and the mental recovery time your brain needs between cognitively demanding work.

- Per week: Keep one half-day (3–4 hours) as a "flex block," scheduled but unassigned. This is where carried-over tasks, surprise priorities, and catch-up work go.

This step directly counters the planning fallacy from Section 2. Buehler, Griffin, and Ross showed that even experienced professionals underestimate task durations (5). The buffer isn't wasted time. It's the difference between a plan that survives contact with reality and one that collapses by Tuesday.

A fully-packed calendar looks productive. It isn't. It's fragile.

A Simple Weekly Planning Template

You don't need a complex system. Here's the framework in one table:

| Step | Time | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Review | 15 min | Audit last week: completion rate, carryovers, surprises |

| 2. Priorities | 10 min | Pick 3–5 specific outcomes for the week |

| 3. Energy map | 5 min | Assign priorities to peak energy hours |

| 4. Implementation | 10 min | Write "when/where/what" for each priority |

| 5. Buffer | 5 min | Add 20% daily buffer + one flex half-day |

Total: ~45 minutes. Do this on Sunday evening or Friday afternoon. Sunday gives you a clear start to Monday; Friday lets you close the work week with closure and spend the weekend free of open loops (which is exactly what Masicampo and Baumeister's research predicts) (1).

One more thing: review your plan briefly on Wednesday. Not to redo it, just to check if your priorities still match reality. A five-minute mid-week checkpoint catches drift before it compounds.

Common Weekly Planning Mistakes

Over-scheduling every hour. If your plan has no white space, it has no resilience. The first unexpected task or meeting overrun breaks the entire system. Treat unscheduled time as a feature, not a failure.

Treating all hours as equal. Scheduling a complex strategy document during your post-lunch dip because "it's the only open slot" is planning with one hand tied behind your back. The circadian research is clear: your cognitive capacity varies by 20–30% across the day (6). Plan accordingly.

Planning tasks instead of outcomes. "Work on marketing" is a task. "Finish the campaign brief with target metrics" is an outcome. Your brain responds differently to each. The goal-setting research shows specific outcomes drive higher performance than vague activity descriptions (3).

Skipping the weekly review. Without data from last week, you're planning from your imagination, which is exactly the "inside view" that causes the planning fallacy (4). Your actual completion rate is the best planning input you have.

Setting 10+ priorities. If everything is a priority, nothing is. Cognitive research on attentional capacity suggests 3–5 active goals is the productive range. Beyond that, you're splitting focus so thin that nothing gets deep attention.

FAQ

What's the best day to plan your week?

Either Sunday evening or Friday afternoon. Sunday gives you a clean mental start to Monday. Friday lets you close open loops before the weekend, which research suggests reduces cognitive carryover into your rest days (1). Try both for a few weeks and see which feels better. There's no research showing one is definitively superior.

How long should weekly planning take?

About 30–45 minutes. If it takes longer, you're probably over-planning, trying to schedule every task instead of focusing on the 3–5 priorities that actually matter. The power is in the specificity of a few goals, not the quantity.

Should I plan every hour of every day?

No. Plan your priorities into specific time slots (implementation intentions), then leave at least 20% of your day unscheduled. Rigid hour-by-hour schedules break on first contact with reality. Your plan should be a framework for decisions, not a minute-by-minute script.

What if my week goes completely off-plan?

That's normal, especially in the first few weeks. Check your completion rate: if you're finishing less than 50% of planned priorities, you're over-committing. Reduce to 3 priorities next week. The weekly review exists to calibrate your planning to your actual capacity over time.

The single most useful thing you can do for your productivity this week takes 45 minutes and zero apps. Sit down, review what happened last week, pick 3–5 things that matter, and give each one a specific time and place in your calendar. The research says that's enough to free your working memory, triple your follow-through on goals, and build a planning habit that actually holds up.

If you want to take it further, Exoplan matches your tasks to your predicted energy levels automatically, turning Step 3 from a manual estimate into a data-driven decision. But the method works with any calendar. Start this Sunday.

References

- Masicampo, E.J., & Baumeister, R.F. "Consider It Done! Plan Making Can Eliminate the Cognitive Effects of Unfulfilled Goals." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(4), 667–683, 2011. PubMed

- Gollwitzer, P.M., & Sheeran, P. "Implementation Intentions and Goal Achievement: A Meta‐Analysis of Effects and Processes." Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 38, 69–119, 2006. ResearchGate

- Locke, E.A., & Latham, G.P. "Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation: A 35-Year Odyssey." American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717, 2002. PubMed

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. "Intuitive Prediction: Biases and Corrective Procedures." 1979. ResearchGate

- Buehler, R., Griffin, D., & Ross, M. "Exploring the 'Planning Fallacy': Why People Underestimate Their Task Completion Times." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(3), 366–381, 1994. APA PsycNet

- Valdez, P. et al. "Circadian Rhythms in Attention." Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 2019. PMC

- Facer-Childs, E.R. et al. "The Effects of Time of Day and Chronotype on Cognitive and Physical Performance in Healthy Volunteers." Sports Medicine – Open, 4(1), 47, 2018. Springer

- Hagger, M.S., & Luszczynska, A. et al. "Implementation Intention and Action Planning Interventions in Health Contexts." Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 6(1), 1–47, 2014. PubMed